Ultra Violette Co-Founder Ava Chandler-Matthews shares her feeding story.

When Art was born, he was really little. Just 2.59kgs at 38 weeks and 3 days. Being so little, we were focused on getting him fed and bigger.

I had read on all the pro-breastfeeding pages, “Don’t let the midwives pressure you to let them give the baby formula,” and “you can say no,” but the reality is when you have a small baby, you want them to be fed and you want them to grow. I felt no pressure in hospital, the paediatrician said, “are you planning on breastfeeding?” I said yes, he said great and they tried to get as much colostrum as they could. They are essentially milking you, but again, I didn’t feel anything negative about that. I wanted that help, I knew they would get everything out of me that they could. I wasn’t making a lot of colostrum. My boobs didn’t actually grow much in pregnancy, a bit, but not a lot. And in the hospital the midwives were all saying, “just wait ‘til your milk comes in,” and kind of laughing, “you’ll know about it,” and I was thinking, oh wow, as someone who's never had big boobs, like, wow, I’m going to wake up one morning with giant boobs, how funny, but it just never happened.

The lactation consultant came by and said, “Yeah well you have that boob shape that can be hard for breastfeeding, and you have that gap in between them, so that might be hard,” I was like, what? She used a phrase I'd never heard, “insufficient glandular tissue (IGT)”, something that could be caused by PCOS. I just thought I had smaller boobs, I didn’t realise that when I hit puberty that PCOS had affected my development. I didn’t even know I had PCOS until I was trying to get pregnant. It was a weird moment, to be living with something your whole life that had affected so much, but not even know about it. And now it impacting my breastfeeding ability.

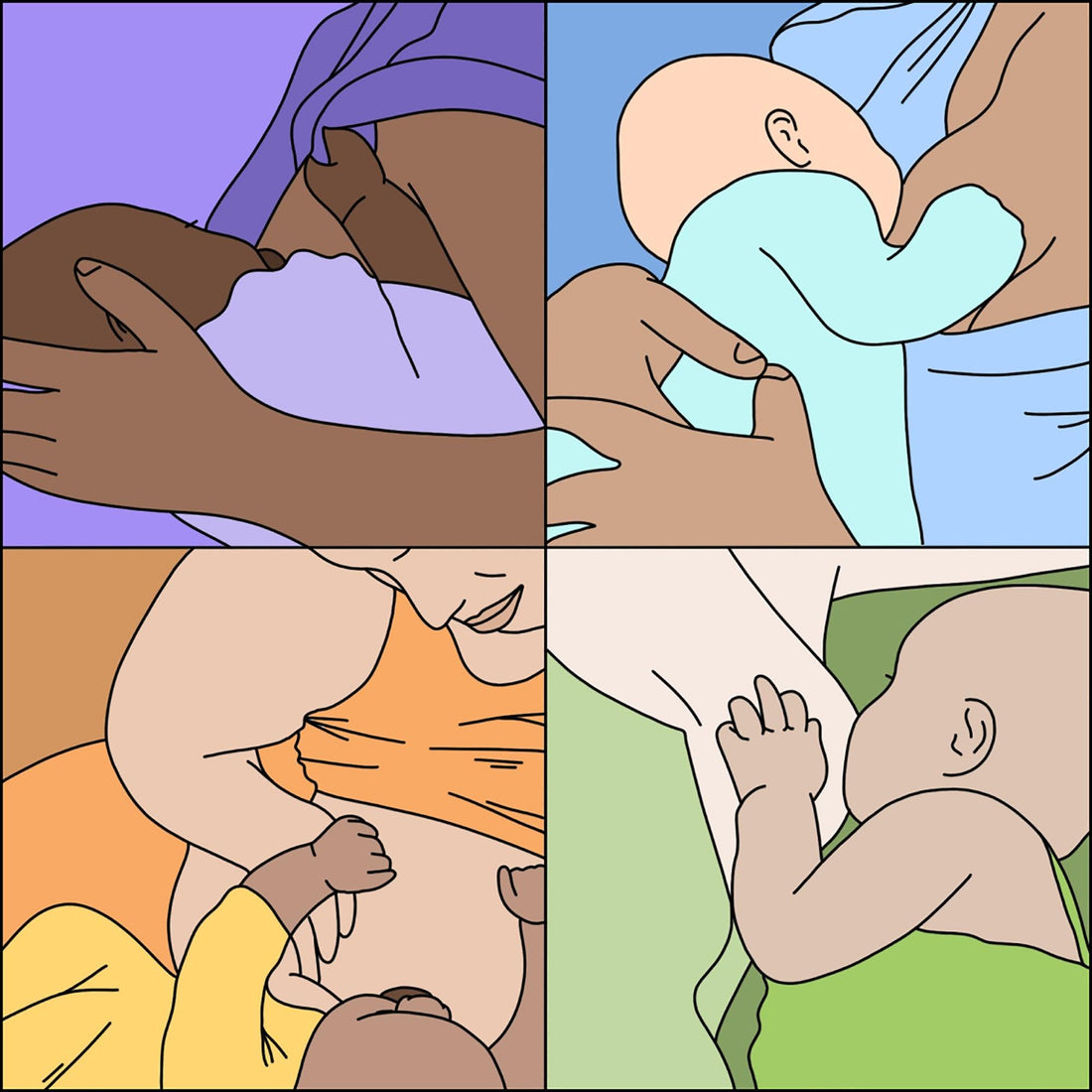

Until my last day in the hospital and I still had that transitional milk, my milk hadn’t come in, but I’d had a Caesarean, which can sometimes make it take longer. However, I just had a feeling it wasn’t going to happen. I just didn’t know if it was going to work out. I wasn’t getting 10mls even with pumping, so he’d started on formula so he could get 30mls. On the last day I woke up not with the big, solid milk boobs I’d heard about, but my nipples had flattened and it was impossible for Artie to latch. The midwife came in and suggested nipple shields. Once at home, we kept trying with the shield, but I was mainly just attached to a pump, every two hours, desperately trying to up my supply. I was spending 20 minutes trying to get him to latch, then feeding, then giving him a bottle and pumping, all of which would take maybe two hours, so I only had an hour before I’d have to do it all again. It was soul crushing.

A good friend called to ask how I was going, and I was sobbing to her that I didn’t have enough milk, and he was struggling to latch. I was saying to her, “I just don’t know how to do this”. She told me I could get a prescription for a medication that can up your supply. My obstetrician gave me a script, and that afternoon I had an appointment with a lactation consultant. She helped me with positions and the latch, and we were having some success, but we kept him on the formula to make sure he was getting what he needed. I’m someone who reads everything and does all the things, so I decided to also see another lactation consultant that was recommended to me by my obstetrician, who said this particular consultant was especially great with small babies. Why have one when you can have two, right?

By this point, feeding had become the bane of my existence. Artie was small and full, so he was sleeping well, but I was just so focused on feeding. It was all I thought about. When the second lactation consultant came, she showed me how to latch without the shields and told me, “OK, we’re going to do a feeding bootcamp.” For two weeks she upped the dosage of my medication, had me triple feeding, every three hours, got me eating more and did everything we could to up my supply, all the while Artie was still happily taking formula top ups. Because he was so small, I never felt comfortable to totally leave it up to what he could get from the boob, I just wanted him to be fed and growing.

The bootcamp time was a bitch, but I did it, and lived to see the other side, but I was never really wanting to exclusively breastfeed, if I could get some breast milk in there, I was happy, but I never needed it to be exclusive. So I was happy with mix feeding. But then, he started showing signs of an allergy or intolerance. He was uncomfortable and crying, having weird poos. I took him to the paediatrician who advised that I needed to come off dairy, and change his formula because he may have a cow’s milk intolerance. A month later I was off dairy, eggs and nuts trying to figure out what was upsetting him. By that stage, I decided it would probably make more sense to stop breastfeeding, because there were so many things that could be causing the allergy. If I stopped breastfeeding, then I’m only dealing with one variable, the formula. So after all that effort, and all that money, it’s looking like we’ll stop breastfeeding soon. It’s something I feel guilty about because with all the specialists and aids and medication, it’s cost me over $3,000 to learn how to breastfeed. The notion we’re told that breastfeeding is easy and cheap is just such a lie. It’s not easy and it’s not cheap, and that’s not even taking into account my time or the toll it’s taken on me. I had to really work at it, and I did have people telling me, I should just let him do breastmilk and cut the formula to better increase my supply because the baby’s more efficient at getting milk out, but I just never felt comfortable tinkering with the reliable food source he was getting, which was formula.

Ava’s Takeaways

You really do need support to be able to feed.

You read a lot about how breastfeeding takes a village, and I’d always thought, how can someone else help you breastfeed? But my mum staying with me meant I had someone to do things for me while I had to sit there and feed or pump. Support isn’t always to physically help you breastfeed, it’s to take care of you so you can focus on breastfeeding. I wouldn’t have been able to do those triple feeds if she wasn’t there making sure I did. She would literally bring the pump to me. She'd bring me a big bottle of water or a cup of tea or like 75 biscuits. She just made sure I was doing it.

There are amazing consultants who tell you the truth.

All my specialists and consultants said the same thing, "the most important thing is that he is fed and you are happy." They reinforced to me that I couldn’t be a good mum if I wasn’t mentally well.

The hormones play tricks on you.

It’s hard to remember once you’re out of it, but your hormones play tricks on you, they are what’s making you feel you must breastfeed and if you can’t do it well that you are doing a disservice to your baby. Your logical brain isn’t working like it usually would.

If you’re not breastfeeding, there’s a real lack of support.

It definitely feels that the support in Australia is only geared towards breastfeeding, and if you can’t or don’t want to there’s not much for you. Advice on formula, or bottles, it’s hard to get that information because all formulas have to be treated equal in accordance with the marketing laws. I was asking for formula recommendations from the lactation consultants and midwives and was told no one could recommend it for me. Trying to read the ingredients on the back is really intense too. It all adds to the pressure you feel to be able to breastfeed, and the literature makes you feel like it's natural so it should be easy. It’s like they don’t say it might not be easy because they don’t want to put you off, but actually, knowing more would help with the expectations.

We should be learning more before we’re in it.

We should have to go see a lactation consultant while you’re pregnant. If I had, I would have known about my Insufficient Glandular Tissue (IGT), and not been waiting for these huge milk boobs to happen. We should also be encouraged to research formulas, so we’re not out shopping for it when we’re most vulnerable.