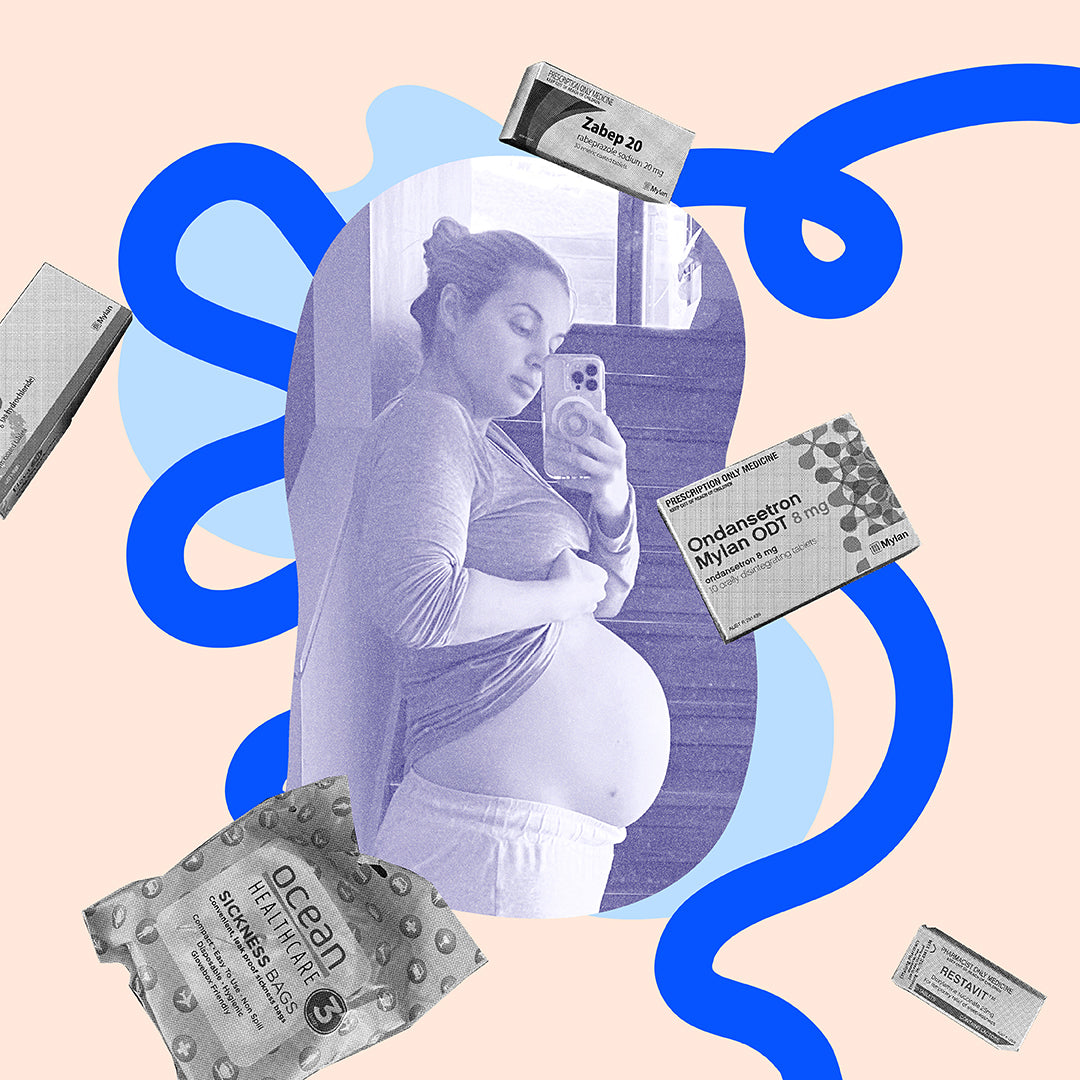

Abbey Gelmi’s journey with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) began the way that it does for most, “I was pregnant and a girlfriend asked me, ‘Oh, have you had that gross sugary drink test yet?’” says the journalist and mother of two boys, Louis (2) and newborn, Oliver. Everyone talks about this sugary drink but not really what it’s for, and I remember my main concern was around how I’d cope with fasting for the test, and if I’d be able to keep it down, as I also had hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) (imagine a hugely severe form of morning sickness that saw Gelmi hospitalised 13 times). For me it was just a checkbox on the list of pregnancy appointments, and I didn’t think about it again because I never considered that I’d be the person getting the call to say, ‘you have diabetes’.” Gelmi recalls the spiral she went into when her obstetrician delivered the news. “I’m so ashamed of my lack of knowledge at the time, but I didn’t know anyone who had it or how it occurred and all I could think was ‘this is my fault’. I felt like I was failing as a mother and my baby wasn’t even Earth-side.” While totally unfounded (GDM is largely a condition caused by genetic factors) Gelmi is not alone in this feeling of guilt, numerous studies have documented that women diagnosed with GDM report feeling responsible for their diagnosis and experiencing feelings of guilt, self-blame, failure, embarrassment, sadness, shame and negative self-talk. It’s understandable, not because there is anything to be ashamed of in having GDM, but because pregnancy is already a time when most women try desperately to be doing things the “right” way. Eating the right things, sleeping on the right side, using the right skin care, taking the right advice, doing things at the right time and learning the right information about birth, postpartum, breastfeeding and newborns… and with all this in your head, you take a leap at one of the earliest hurdles (the GD test), and (seemingly) fail.

Not wanting to be blindsided again, Gelmi decided to learn. “When I feel out of control in my life, I try to use information to bridge the gap. I studied for pregnancy like I was about to do a PhD.” One of the key things she learnt? Gestational diabetes typically ends when your baby is born and, while it seems to be absent from the growing pregnancy discord on social media, it is common. It’s generally reported that between 1 in 10 and 1 in 20 pregnancies are affected by gestational diabetes, but in 2016–17, the AIHW found around 1 in every 7 women aged 15–49 who gave birth in hospital were diagnosed with gestational diabetes. In other words, 15% or 40,800 women. Prevalence has tripled since 2000-2001, however changes in diagnostic guidelines have impacted that number.

What puts you at higher risk of developing gestational diabetes?

While the specific cause of GDM is unknown, the prevailing theory is that the placenta — the organ that delivers water and nutrients to the fetus — produces hormones that block the mother's ability to use insulin effectively. Its occurrence is described as complex, resulting from a combination of genetic, health, and lifestyle factors, some of which have not been identified. Despite this, there are certain criteria which can put you at risk. Women with GDM are more likely to be:

- Older. Women aged 45–49 were more than 4 times as likely to be diagnosed with gestational diabetes as women aged 15-19. A 26% chance compared to 6%.

- Have a family history of type 2 diabetes.

- Born in Southern and Central Asia — incidence among these women was more than twice that of Australian-born women (28% and 13%, respectively).

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander — women of an Indigenous background were 1.3 times more likely to have GD than non-Indigenous women.

- Socioeconomically disadvantaged — women from the lowest socioeconomic group were 1.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with gestational diabetes than women in the highest socioeconomic group (19% and 13%, respectively).

- Diagnosed with gestational diabetes in a previous pregnancy, or had a large baby in a previous pregnancy.

- Have polycystic ovary syndrome.

- Be taking some types of antipsychotic or steroid medicines.

However many women diagnosed with GD do not meet any of the criteria. In her first pregnancy, Gelmi met none, and in her second, she only met that she’d had it in her first.

I have gestational diabetes, now what?

If you are diagnosed with gestational diabetes, you will explore a treatment plan with your doctor to manage the condition. In 2016–17, more than half (56%) of women with gestational diabetes managed their condition through the use of diet, exercise and/or lifestyle management. Around a third (32%) required insulin therapy while 8% were treated with oral hypoglycaemic (blood glucose lowering) medications—5% was unspecified. After receiving her own diagnosis, Gelmi and her partner Kane Lambert went to meet with a specialist diabetes nurse named Lois. “Before she’d even looked at my file or knew my name she said, ‘Hi! This is not your fault. It’s not the croissant you had in the first trimester. It’s not the banana bread you had yesterday. You are genetically disposed to have this. We have wonderful medicine that can help and if you end up on insulin, you've not failed. Have I mentioned this is not your fault.’ And I just burst into tears and it was just everything I needed to hear.” Gelmi is hugely grateful to have had that experience, “There are so many wonderful medical professionals that you meet through this journey where you realise it's their vocation. They were put on the earth to calm people during those scary moments. I was so lucky that Lois was the person who sat opposite me.”

Gelmi was given a plan of how to handle the next 10 or so weeks of her pregnancy, including how to monitor her blood sugars. Something which is constant, to say the least. “You test yourself by using a finger prick machine and that then reads your blood sugars. You do it when you first wake up, then two hours after breakfast, two hours after lunch and two hours after dinner. And that's from when you take your first mouthful.” Meals had to be finished within 30 minutes and snacks timed to not produce an inflated reading.

For Gelmi, it sparked a challenge she hadn’t foreseen. “I’d certainly gone through periods of my life when I’d been really unhealthily restrictive with what I’d ate and it brought up all these formally unhealthy habits. It’s something I’d done a lot of work to help me no longer be that person, and suddenly I was being told by a doctor that I had to stabilise my weight, and count carbs for the sake of my baby. It was overwhelming, and because of the readings I was getting, I ended up keeping a very strict food journal.” Despite the restrictions, Gelmi’s overnight fasting levels were still high, so she was put on insulin for the evenings. “That was a big mental trigger. I blamed myself for not being able to control it with my diet. I wondered if I’d not been diligent enough or strict enough. And even aside from that, in my experience, being carb-free is miserable, particularly when you’re pregnant and exhausted. It’s just not sustainable. It took me a while to accept this was not something I could control, but eventually I realised that taking insulin was the best thing I could have done.” Gelmi also assures that the insulin needles are very manageable. “They’re so fine, literally, and you just shove it into the fleshiest part of the upper thigh you can find.”

The mental load of GDM

“So much of pregnancy is anxiety inducing, but a lot of it is gray,” says Gelmi. “You have an idea of what you should be doing but it’s individual or there are a million little pros or cons that balance it out. The difficult thing about gestational diabetes, particularly for perfectionists or people with anxiety or obsessive tendencies, is that you are getting concrete results. Every two hours, a little machine tells you in a numerical, very quantifiable, way if your last meal decisions made you fail or pass.” A short mental leap to being told you’re failing or passing as a mother. Then there’s the public perception of gestational diabetes. “Anytime I share something about gestational diabetes on social media, two things happen,” says Gelmi. “1, I get comments like, ‘Oh, but you’re not unhealthy!’ from people who don’t understand the condition, and 2, I’m overwhelmed with women thanking me for sharing because they are sick of telling people that they don’t have GDM because they’re unhealthy.”

What happens when it’s time to have your baby?

Women with gestational diabetes are at a higher risk for preeclampsia (hypertension during pregnancy), problems with labour, and Cesarean delivery. A large baby (considered more than 9 pounds at delivery) may cause injury to the mother during a vaginal delivery. A very large baby may suffer broken bones or nerve damage during delivery. Though the occurrence of these are very rare. However, for these reasons, GD mums are heavily monitored in the last weeks of pregnancy, and are often encouraged to plan an early birth (usually elective induction) at or near term instead of waiting for labor to start on its own. The close monitoring is to determine the best time for this to happen.

What happens once your baby is born?

High blood glucose during labor can cause complications for the baby, including chemical imbalances. But one of the main concerns is hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, in the baby immediately after delivery. This occurs if the mother's blood sugar levels have been high, which spikes the insulin level in the fetus’s circulation.

After delivery, the baby still has a high insulin level, but without the high sugar level from the mother. This causes the newborn’s blood sugar level (measure via heel prick) to become too low, and glucose may need to be administered intravenously.

To avoid this, blood glucose is monitored very closely during labor. Insulin may be given to keep the mother's blood sugar in a normal range to prevent the baby's blood sugar from dropping excessively after delivery.

For most women, blood glucose levels return to normal after delivery. This is when you can crack out that well-earned croissant. You will need to take the glucose test again — Yes, that delightful drink again — at about six weeks postpartum, and every two-years after that. This is to ensure there is no sustained type 2 diabetes.

What to remember about gestational diabetes

If you have it, Gelmi wants you to remember that you’re not alone. “You're one in seven pregnancies. You're not alone, it's not your fault and the stigma is ridiculous. And if you have diabetes as a general condition, my goodness, you’re warriors.”

-(1)-v1737717053430.png?1080x1350)

One more time, what is the glucose screening test?

This is the “yucky drink” test you’ve heard about from your mum friends, officially known as the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Your doctor will refer you to take it between 24 and 28 weeks (or sooner if you are at higher risk), at your GP or hospital, to check for gestational diabetes.

You arrive for the test with an empty stomach (so book the earliest appointment you can), they take your blood from your arm to check your blood sugar level. This is to get your baseline level. Then you swig a super sweet, kinda gross, solution that contains 75 grams of glucose (do it fast). Hang in the waiting room (bring a book/headphones or something to entertain you - and note that these places have notoriously bad WiFi reception). After an hour, you’ll have your blood taken again to check your new blood sugar level, and once more after another hour. The goal is to gauge how efficiently your body processes sugar. It can be a really long and awful test for some, others find it boring, but fine. If you start feeling nauseous or faint, speak up and ask that they let you lie down in an examination room. After the final blood sample, you get to leave and finally eat (plan to do something chill and comforting, as it can make you feel really off). The results should be available in a few days and your doctor will either call you to share them or speak to you about it in your next appointment. If one of these 3 blood glucose values is higher than the laboratory range, you will be diagnosed with gestational diabetes.