Mastitis is one of the scary new parent words that goes around new mum Whatsapp groups and is always on the minds of anyone trying to establish breastfeeding. It's also incredibly common. One in five Australian mothers will develop mastitis, and it is most likely to occur in the first four to six weeks after birth. How we understand mastitis greatly shifted in 2024, which impacted recommendations of treatment in a big way. “These guidelines have significantly changed the way that we diagnose and treat mastitis,” says Dr Amber Hart, GP, IBCLC and Founding Director of Maternal & Infant Wellbeing Melbourne. It is not a guarantee that your own health care provider will be up to date on these new guidelines, so it's worth being informed yourself. Ahead, everything you need to know about understanding mastitis and how to treat it.

Understanding Mastitis

Until recently, mastitis was thought to be caused by a blockage in the breast. The advice was to apply heat, massage out lumps, feed more often, and always start the baby on the affected side. “Prior to these guidelines coming out, we thought mastitis was related to a blockage in the breast," explains Dr Hart, "From what we now know from research in the area, this is actually not the way that we should be managing these inflammatory conditions,” explains Dr Hart. "We now know that engorgement, blocked ducts, mastitis and breast abscesses are not separate issues, but part of the same condition — just at different stages."

What’s Really Happening in the Breast

Mastitis is primarily an inflammatory condition, triggered when milk isn’t draining properly or when there’s pressure on the breast — from tight clothing, sleeping positions or the wrong pump flange size. “What happens is that those glands in that segment of the breast get over full of milk, the little junctions in between get leaky, and milk leaks into the space around those glands. That sets off an inflammatory response… which causes warmth, firmness and tenderness,” says Dr Hart. "It usually begins as a sore patch, maybe a lump or wedge of firmness, while you otherwise feel well. This is what we call inflammatory mastitis.”

First, Fix the Cause

"The most important thing is to identify and fix the reason it happened in the first place," says Dr Hart. "For this, you need to see a Lactation Consultant. It is incredibly important that the underlying cause is addressed, because if you only treat the symptoms, you're only band-aiding the problem. Make sure you get in touch with a breastfeeding specialist,” says Dr Hart.

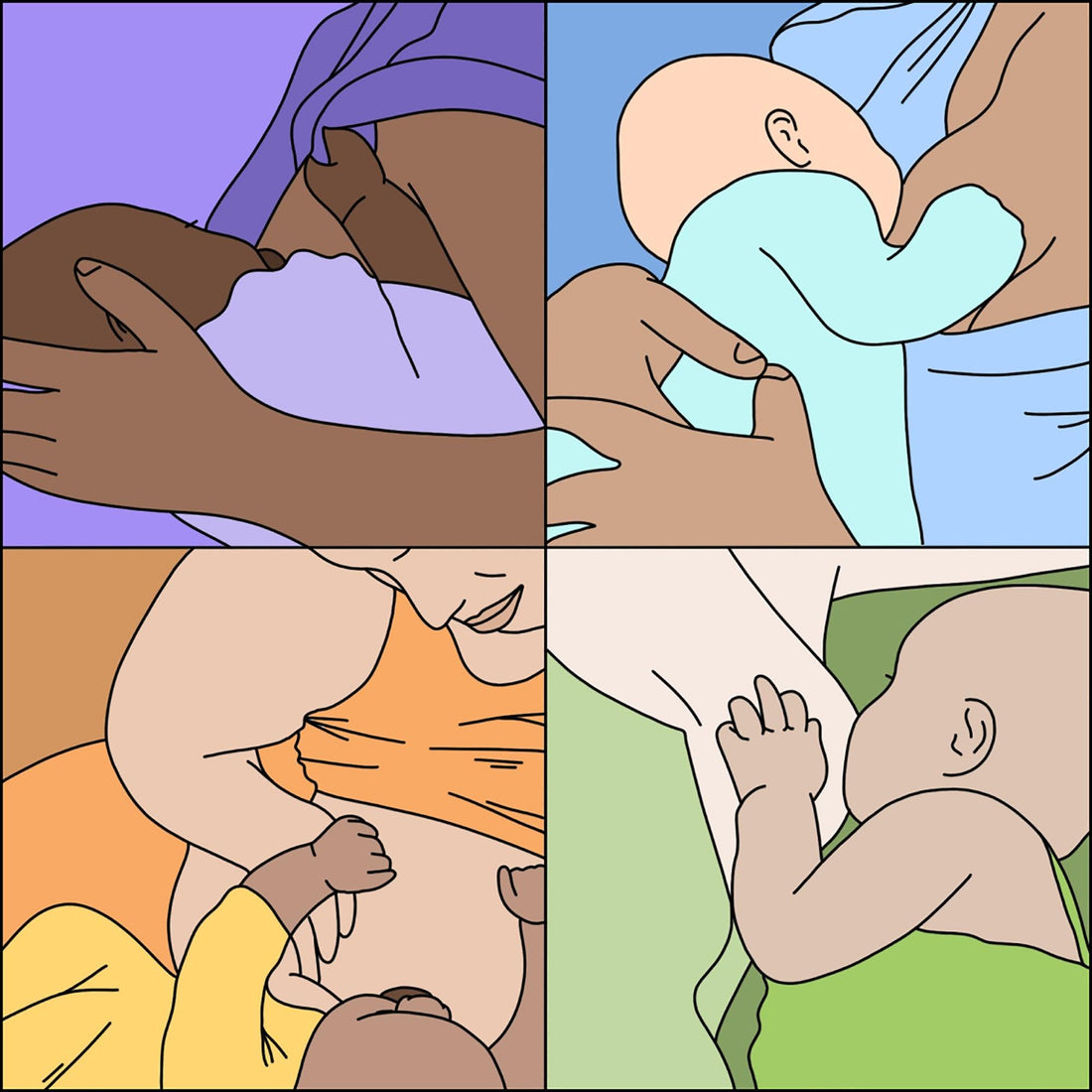

Enter Physiological Feeding

If you have a lump or tenderness but are otherwise feeling quite well, the new approach is to do what's called physiological feeding, but it generally means to keep things as normal as possible. “We just do what the baby would normally do on that breast. We don’t increase the frequency of the feeds but we also don’t decrease them,” says Dr Hart. The, like any inflammatory process, the focus is on reducing swelling. “We treat it pretty much like a sprained wrist… we apply cold to the breast after a feed. We take regular anti-inflammatory medication if it’s medically safe for you to do so. It is okay to take ibuprofen while you are breastfeeding.” There is also some massage, but it looks different to what it used to under the new guidelines. “We no longer recommend really getting in and kneading out those lumps. It’s now lymphatic massage, which is more of a gentle patting, stroking towards the armpit,” she explains. A little warmth just before a feed, if it is helpful in triggering your letdown is OK, but overall, heat is discouraged. “Complete opposite to what we used to tell people.”

When to Consider Antibiotics

The aim is to settle symptoms within 12–24 hours. “If we can clear that blockage in 12 to 24 hours with physiological feeding and you're feeling comfortable, then we can avoid use of antibiotics. But if the symptoms are progressing rapidly… more sore, more firm, more red, you’re starting to feel more unwell, we will get you on antibiotics quite quickly,” says Dr Hart. Previous guidelines would delay antibiotics.

If you've been accustomed to the old way of treating mastitis, it might take a beat to stop thinking about it as a clog in a pipe, but rather as swollen tissue around a pipe that might be making it tighter. Treating it like a sprain that needs care, rather than hole you need to force something out of, makes a lot of sense if you've ever experienced mastits yourself. One of the biggest differences in how we address it, which is also one of the most logical, is getting to the root of the issue under the assessment of a breastfeeding specialist. Fixing the cause will go a lot further in reducing the chance of recurrence, and as any mum whose experienced mastitis will tell you. It is not something you want to happen more than once.